Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Performance: Revolution Televised and the Emperor's Gaze

Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show transformed a spectacle of empire into an act of defiance, evoking echoes of ancient Rome to hold a mirror up to modern America.

For centuries, rulers have understood that spectacle is not just entertainment—it is governance. The Roman emperors mastered this art, using theatre, games, and grand performances to maintain control, to dazzle and distract even as the empire’s cracks deepened. And in that tradition, the Super Bowl halftime show stands as one of America’s most elaborate modern spectacles—a moment in which culture, politics, and power converge under the emperor’s watchful eye.

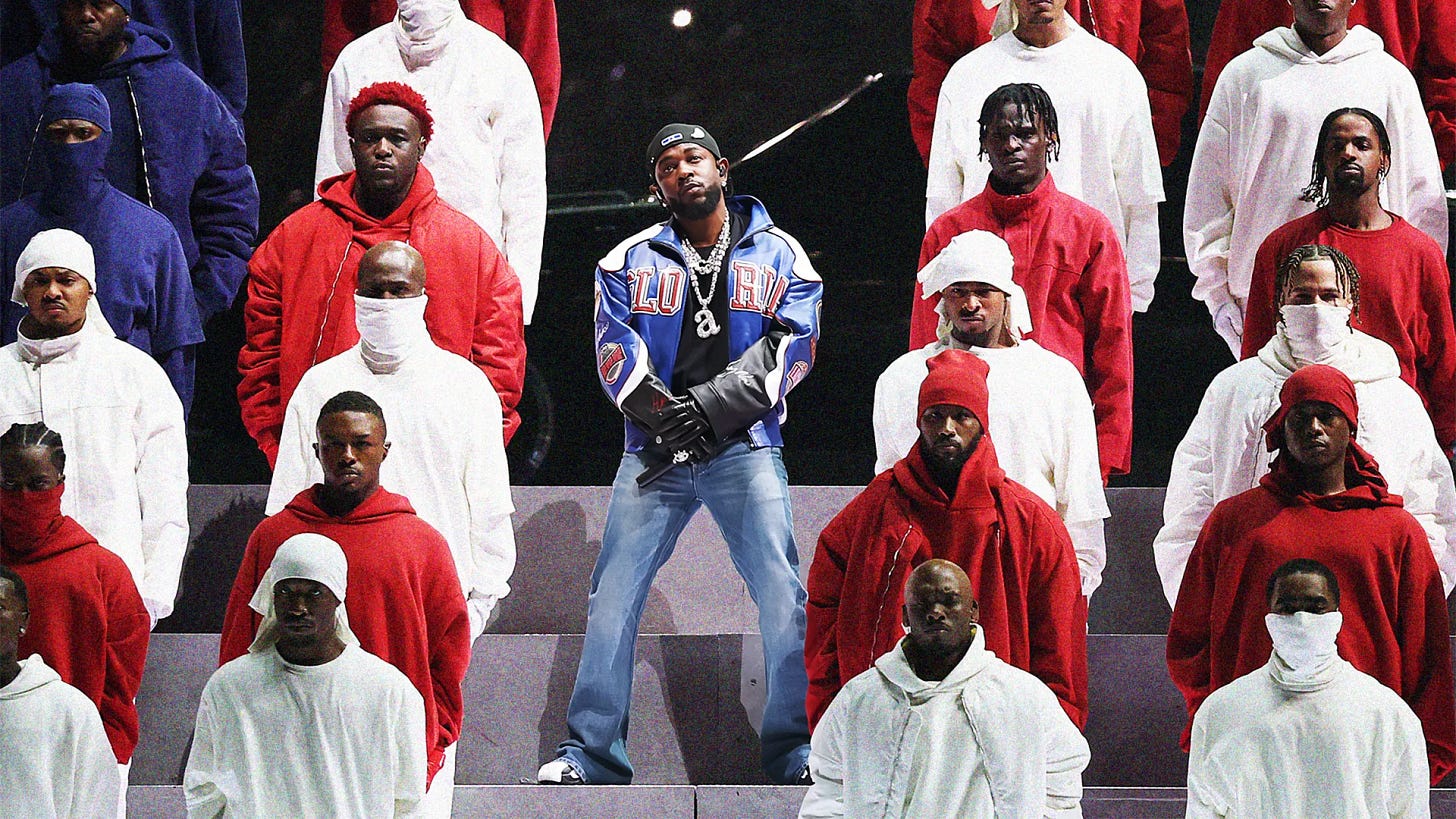

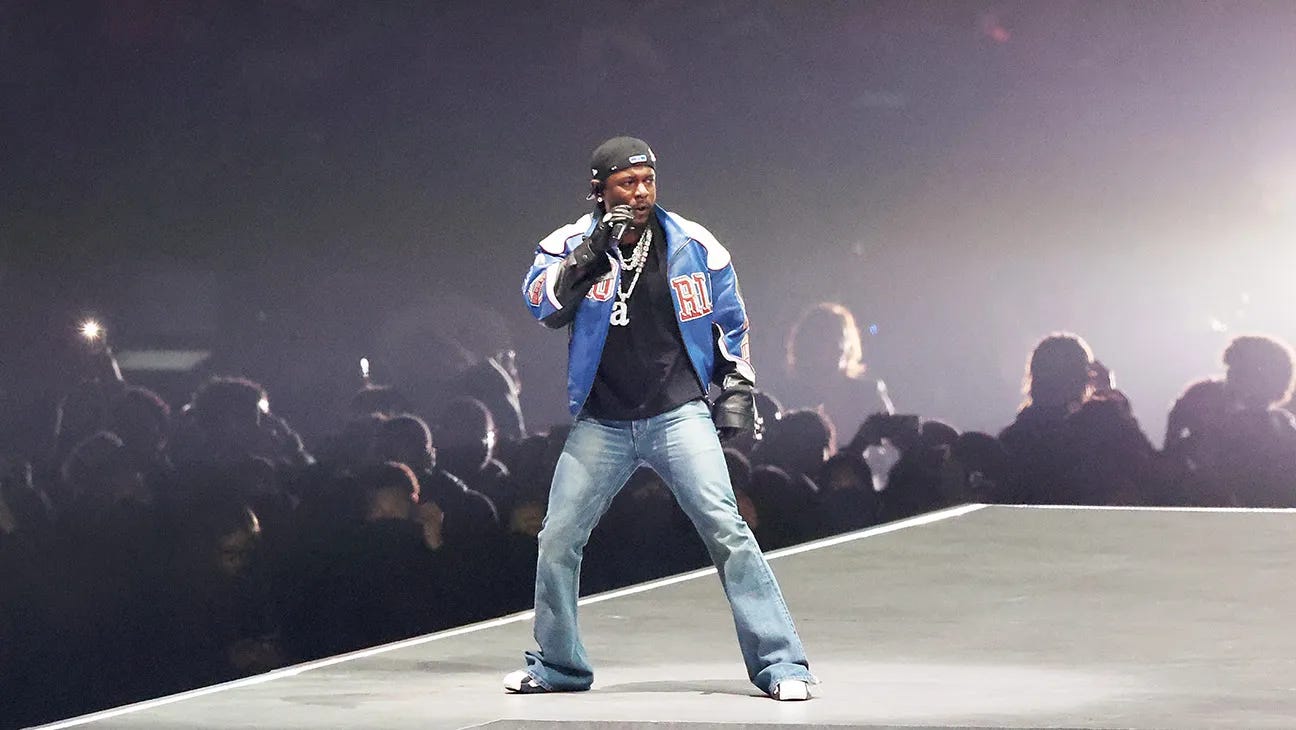

Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime performance was nothing short of electrifying — a powerful testament to his artistry and cultural commentary. In a space often reserved for feel-good anthems and sanitised entertainment, Lamar stood defiant, unapologetically Black, and unashamedly political. With a legion of dancers clad in red, white, and blue, Samuel L. Jackson embodying “Uncle Sam,” and a setlist that leaned heavily on his most recent work, Lamar’s performance transcended music to become a potent critique of the American empire.

And yet, it was performed in front of the modern-day emperor — Donald Trump — seated in the VIP section, presiding over a spectacle reminiscent of ancient Rome’s gladiatorial games. The echoes were undeniable: emperors, too, understood the political power of spectacle. They appeared at theatre and games, greeted by roaring crowds whose passions were channelled and pacified by grand performances, distractions from the fractures within the empire.

Trump, like the emperors of old, presided over the event with a gaze that seemed to demand deference. In Rome, the emperor’s presence at the Colosseum was a reminder of his supremacy—of his power to grant life or death with a mere gesture. In the VIP box at the Super Bowl, Trump’s presence carried a similar weight, a tacit assertion that the empire, no matter how fractured, still belonged to him.

The Super Bowl itself is, in many ways, America’s modern-day panem et circenses—“bread and circuses.” The phrase, coined by the Roman satirist Juvenal, describes how emperors pacified the public with food and entertainment rather than addressing deep societal fractures. This is the logic of empire: keep the people dazzled, keep them entertained, and they will not revolt. Yet Lamar did not simply entertain; he used the spectacle against itself, forcing an uncomfortable confrontation with the very issues the empire seeks to suppress.

From the moment Samuel L. Jackson, clad as “Uncle Sam,” opened the show with a sardonic “Salutations...and this is the great American game,” it was clear this would not be a sanitised patriotic affair. Lamar stood on the hood of a black Grand National, declaring, “The revolution ’bout to be televised,” while an all-Black ensemble of dancers decked out in red, white, and blue performed behind him—a bold reimagining of the American flag.

His message was clear: America’s fractures are not to be hidden but exposed. Uncle Sam, played with biting satire by Jackson, scolded him for being “too loud, too reckless, too ghetto,” echoing the criticisms often hurled at Black artists who refuse to play by the rules of respectability politics. Lamar’s response? A defiant “You picked the right time but the wrong guy.”

Unlike many previous halftime shows that relied on nostalgia and safe singalongs, Kendrick’s set list was daringly current, drawing heavily from his latest California-soaked album GNX. He chose tracks that wrestled with race, power, and cultural division rather than leaning on past hits. There was no retreat into the comforting echoes of good kid, m.A.A.d city or To Pimp a Butterfly. Instead, Kendrick pushed forward, resolute in his artistic vision.

Roman emperors understood that keeping the populace entertained was essential to maintaining power — “A people that yawns is ripe for revolt,” as historian Jérôme Carcopino observed. But Kendrick subverted the spectacle, transforming it into a critique of the very empire that had invited him to perform.

As Lamar rapped, “It’s a cultural divide, I’ma get it on the floor / 40 acres and a mule, this is bigger than the music,” he laid bare America’s unfulfilled promises and persistent exploitation of Black culture. This performance was already historic as the first Super Bowl halftime show led by a solo rapper, a significant milestone given the NFL’s complex relationship with Black culture and hip-hop music.

This moment was not just a performance—it was protest art, reminiscent of Roman satire, which often used humour and irony to critique societal and political issues. Like Juvenal, Lamar wielded performance as a blade—cutting through patriotic pageantry to expose the contradictions at the heart of the empire. If satire in Rome was a tool of defiance, Lamar’s show functioned in much the same way, turning the halftime stage into a site of resistance.

Lamar’s artistry also could be likened to that of Livius Andronicus, both a poet and also regarded as the father of Roman drama. Both artists used their platforms to craft narratives that challenged the status quo. Andronicus, a highly educated Greek slave turned Roman playwright, was a cultural translator who brought Greek theatrical forms to Roman audiences. Similarly, Kendrick, a descendant of enslaved Africans, has taken the traditions of Black music and storytelling and elevated them to a form of high art, earning him accolades like the Pulitzer Prize.

Furthermore, in ancient Rome, performers occupied a precarious social position. They were simultaneously celebrated and marginalised, much like Black artists in America today. The Roman theory of “extramission,” which held that the eyes emitted rays that touched whatever they beheld, complicated perceptions of performers. To be seen was to be touched, and to be paid for this visibility placed performers on the same social plane as prostitutes. Yet emperors and elites still flocked to their shows, drawn by the irresistible allure of spectacle.

Kendrick’s performance, viewed through this Roman lens, becomes even more profound. He stood in the midst of an American empire that often commodifies Black creativity while denying Black humanity. His halftime show was both an artistic triumph and a political act, refusing to play the game by the emperor's rules.

As the crowd roared and Uncle Sam’s voice faded into the background, Kendrick's message was clear: this was not just a performance, but a reclamation of space, power, and narrative. In that moment, he was not just a performer under the emperor’s gaze—he was a revolutionary, standing defiantly at the centre of the spectacle, reminding us all that the revolution would be televised.

But there’s the tension that cannot be ignored: this performance took place under the banner of the NFL, an institution steeped in racism. The same NFL that blackballed Colin Kaepernick for kneeling during the national anthem, that has historically struggled to provide Black leadership opportunities, and that continues to prioritise patriotism as a brand of compliance. Why would Lamar — a man who has built his career on challenging the status quo — agree to perform on their stage?

Perhaps that’s precisely the point. Black artists in America have long navigated this precarious space, using every available platform, even those built by systems that oppress them, to speak their truths. Arguably, Lamar didn’t legitimise the NFL; he co-opted their stage and made it his pulpit. But of course, even as Lamar pushed the envelope, performing on a stage that ultimately required approval meant that, to some degree, he had to operate within the boundaries of what the empire would allow. And perhaps that is the nature of living within an empire—resistance and complicity always exist in uneasy tension.

In addition, there was the protestor who briefly held up Sudanese and Palestinian flags before being tackled by security. Though fleeting, that moment spoke volumes. It reminded viewers that America’s empire extends far beyond its borders — actively oppressing, destabilising, and silencing countless voices around the globe. This wasn’t just a show about Black liberation; it became a reckoning with imperialism in all its forms.

Lamar’s halftime show was both complicit and revolutionary, celebratory and defiant. Art has always thrived in paradox. It reminded us that Black artists navigating the empire are always balancing on a tightrope — questioning their place within it while using every available tool to uplift their people.